Alexander Graham Bell - Grandfather of the iPhone

When Alexander Graham Bell was 23, what everybody talked about, the way we talk about the Internet now, was the telegraph. Sure, it was faster than the post, but it still allowed only one message at a time to be sent in either direction. Bell was one of many young men determined to improve the new technology – to invent the telegraph 2.0, you could say.

When he was 16, he and his brother had built a talking head that said “Mama” when they blew air through its lips. His family then emigrated from Scotland to Canada, and he opened a school for the deaf in Boston and taught at Boston University. With a grandfather, a father and an uncle who were all elocutionists, it’s no wonder “Aleck” went on to become a speech teacher. (He later tutored the young Helen Keller, and later still the decibel, a measurement of sound volume, was named for him.)

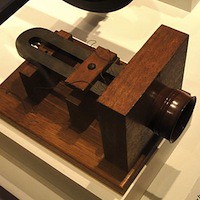

Yet, ever since that talking head, what Bell really wanted to do was keep experimenting with sound. So, in 1873, he set up a laboratory with the help of investor friends. Being more of an ideas man than an engineer, he hired electrician Thomas Watson to construct the actual models based on his theories. A still-unresolved controversy alleges that Bell may have lifted a key idea from fellow inventor Elisha Gray, since lawyers for both parties filed papers at the U.S. Patent Office on the same day in 1876, describing similar methods for “transmitting vocal or other sounds” using electricity and water. However, Bell’s was an actual patent application whereas Gray’s was a statement of intent to file an application. By no means were they the only two to spend years trying to turn the human voice into electrical signals.

On Bell’s 29th birthday, he received word that he would be granted the patent. Exactly a week later, it was March 10, 1876. Bell’s lab notebook, one of hundreds of his papers preserved at the Library of Congress, describes the historic experiment:

Bell’s invention allowed sender and receiver to communicate directly, their actual voices – not dots and dashes – traveling through meters and meters of electric wires. Exciting! Nonetheless, the president of telegraph giant Western Union scoffed at it, calling the telephone nothing but a toy. He showed no interest in buying Bell’s patent, and thus was established the Bell Telephone Company, which became a telecom giant in its own right.

It may be a toy in the hands of kids today, but for more than a hundred years, the telephone was serious business. The wires stretched over longer and longer distances: between Boston and Cambridge in October that year; New York and Chicago in 1892. By 1915, Bell and Watson were on the telephone again, this time publicly demonstrating the first call made from New York to San Francisco, more than 3,000 miles away.

Today, according to the Pew Research Center, people around the world use smartphones more for text messaging than making voice or video calls. Just the other day, when I was running late for a lunch meeting, I sent my friend a WhatsApp message instead of calling her. She only received the message at the end of our meeting. Ironic, isn’t it, that we’ve reverted to sending one message at a time, like in the days of the telegraph?

Still, the invention of the telephone paved the way for the construction of the Internet, and it’s thanks to the Internet and the World Wide Web that we can actually hear Bell’s voice. Not from the famous phone call, of course, but in a 5-minute recording he made nine years after that. The recording was restored by the Smithsonian Institution more than a century later. It’s mostly Bell reading dull lists of numbers, but I think it’s remarkable that we get to hear him say his full name at the end, in his own voice, from a time when people still traveled in carriages and ships.

Sure, Bell may have stood on the shoulders of fellow inventors, but that is the way scientific breakthroughs work. Today he is listed as not only one of the top 10 scientists in Scottish history but one of the 100 Greatest Britons, Canadians and Americans.

When he was 16, he and his brother had built a talking head that said “Mama” when they blew air through its lips. His family then emigrated from Scotland to Canada, and he opened a school for the deaf in Boston and taught at Boston University. With a grandfather, a father and an uncle who were all elocutionists, it’s no wonder “Aleck” went on to become a speech teacher. (He later tutored the young Helen Keller, and later still the decibel, a measurement of sound volume, was named for him.)

Yet, ever since that talking head, what Bell really wanted to do was keep experimenting with sound. So, in 1873, he set up a laboratory with the help of investor friends. Being more of an ideas man than an engineer, he hired electrician Thomas Watson to construct the actual models based on his theories. A still-unresolved controversy alleges that Bell may have lifted a key idea from fellow inventor Elisha Gray, since lawyers for both parties filed papers at the U.S. Patent Office on the same day in 1876, describing similar methods for “transmitting vocal or other sounds” using electricity and water. However, Bell’s was an actual patent application whereas Gray’s was a statement of intent to file an application. By no means were they the only two to spend years trying to turn the human voice into electrical signals.

On Bell’s 29th birthday, he received word that he would be granted the patent. Exactly a week later, it was March 10, 1876. Bell’s lab notebook, one of hundreds of his papers preserved at the Library of Congress, describes the historic experiment:

Mr. Watson was stationed in one room with the receiving instrument.… The transmitting instrument was placed in another room and the doors of both rooms were closed.

I then shouted into [the mouthpiece] the following sentence: “Mr. Watson – Come here – I want to see you.” To my delight he came and declared that he had heard and understood what I said.

Pages 40-41 of Bell’s lab notebook [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Bell’s invention allowed sender and receiver to communicate directly, their actual voices – not dots and dashes – traveling through meters and meters of electric wires. Exciting! Nonetheless, the president of telegraph giant Western Union scoffed at it, calling the telephone nothing but a toy. He showed no interest in buying Bell’s patent, and thus was established the Bell Telephone Company, which became a telecom giant in its own right.

It may be a toy in the hands of kids today, but for more than a hundred years, the telephone was serious business. The wires stretched over longer and longer distances: between Boston and Cambridge in October that year; New York and Chicago in 1892. By 1915, Bell and Watson were on the telephone again, this time publicly demonstrating the first call made from New York to San Francisco, more than 3,000 miles away.

Today, according to the Pew Research Center, people around the world use smartphones more for text messaging than making voice or video calls. Just the other day, when I was running late for a lunch meeting, I sent my friend a WhatsApp message instead of calling her. She only received the message at the end of our meeting. Ironic, isn’t it, that we’ve reverted to sending one message at a time, like in the days of the telegraph?

Still, the invention of the telephone paved the way for the construction of the Internet, and it’s thanks to the Internet and the World Wide Web that we can actually hear Bell’s voice. Not from the famous phone call, of course, but in a 5-minute recording he made nine years after that. The recording was restored by the Smithsonian Institution more than a century later. It’s mostly Bell reading dull lists of numbers, but I think it’s remarkable that we get to hear him say his full name at the end, in his own voice, from a time when people still traveled in carriages and ships.

1885 recording of Bell’s voice, via the Smithsonian YouTube Channel

Sure, Bell may have stood on the shoulders of fellow inventors, but that is the way scientific breakthroughs work. Today he is listed as not only one of the top 10 scientists in Scottish history but one of the 100 Greatest Britons, Canadians and Americans.

You Should Also Read:

Speaker Phone Etiquette

The Internet ~ The World Wide Web

What Is Website Traffic - Definition

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Lane Graciano. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Lane Graciano. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Lane Graciano for details.